Teloi: Part I

Τέλοι μου My Goals

I: Read Homer’s Odyssey in Greek Before Nolan’s 2026 Film

Muse! Help me reach this end – not in twenty years, but in 500 days, to be exact.

I first read Homer’s Odyssey in eighth grade. We read Allen Mandelbaum’s translation, an attempt to translate the Odyssey into lyrical verse. My uninformed eighth-grade self cared little about the nuances of translation (how could I when I hadn’t yet studied ancient Greek?) and instead was focused solely on how different the narrative of the text sounded in comparison to a modern novel. The epithets of gray-eyed Athena and the wine-dark sea became familiar, and while the language might have felt plain, the plot was exciting when I actually stopped to think about it.

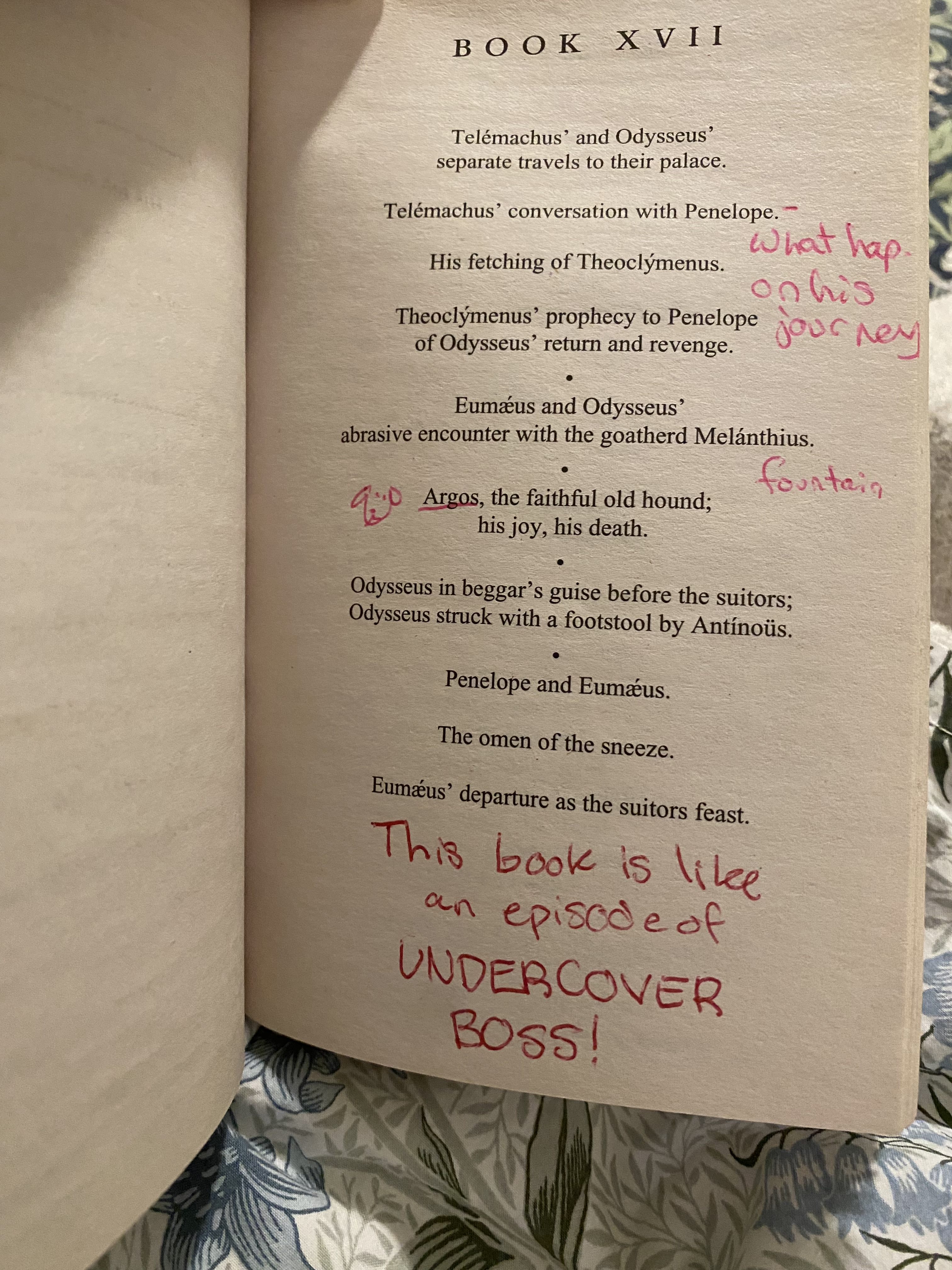

I still have that same copy, complete with the sloppy annotations from my 13-year-old self, my favorite of which is a marginal note at the beginning of Book XVII which reads, “this book is like an episode of UNDERCOVER BOSS!” Even now, I grin at the thought of a skit similar to the one SNL did for Star Wars, when Kylo Ren went undercover as a radar technician for Starkiller Base.

Imagine the disguise “makeover” by Athena, the cutaway scenes of a fear-stricken Eurycleia – trembling to say anything after Odysseus threatened to kill her if she would reveal his identity–, the arrow-shooting contest, and the campy music playing as Odysseus slaughters the suitors en-masse. Perhaps Christopher Nolan or SNL would entertain the imagination of a random Latin teacher while he still has the cast together.

Although I do not remember many of the in-class discussions from that eighth-grade year, Mandelbaum’s translation of the invocation to the muse has stuck with me:

Muse, tell me of the man of many wiles,

the man who wandered many paths of exile,

after he sacked Troy's sacred citadel...

In part this is because we had to memorize and recite it (I remember voluntarily choosing to recite it nearly a week before the deadline), but the lyric translation is done particularly well. I have highlighted the aspects that stick out to me (alliteration, rhymes, etc.):

Muse, tell me of the man of many wiles

the man who wandered many paths of exile,

after he sacked Troy's sacred citadel.

He saw the cities--mapped the minds--of many;

and on the sea, his spirit suffered every

adversity--to keep his life in tact;

to bring his comrades back. In that last task,

his will was firm and fast, and yet he failed:

he could not save his comrades. Fools, they foiled

themselves: they ate the oxen of the Sun,

the herd of Hélios Hypérion;

the lord of light requited their transgression--

he took away the day of their return.

Muse, tell us of these matters. Daughter of Zeus,

my starting point is any point you choose.

My older brother attended the same school and also had to memorize and recite the invocation eight years prior. But when I came across his old school notes when my family moved, I was disappointed by this strikingly plain translation. Unfortunately, I have no way of knowing the translator because the excerpt had been printed on a loose piece of paper without any source attribution, and it was eventually discarded. To this day, I wonder if it happened to be a more literal translation of the original Greek, rather than a more creative one like Mandelbaum’s.

Fast forward seven years to the winter semester of my junior year (2023). I was officially a classics major enrolled in GR-202: Homer. Specifically, the Odyssey. Understandably, the professor required students to have Richmond Lattimore’s translation, as this is more faithful to the original Greek. We read Lattimore’s full translation before translating maybe a third(?) of the text from the original Greek. For part of the final exam, we recited the invocation to the muse in Greek. My own odyssey in the classics had come full circle:

Ἂνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, Μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσε: πολλῶν δ᾽ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, πολλὰ δ᾽ὃ γ᾽ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν, ἀρνύμενος ἣν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων. αὐτῶν γὰρ σφετέρῃσιν ἀτασθαλίῃσιν ὄλοντο, νήπιοι, οἵ κατὰ βοῦς Ὑπερίονος Ἠελίοιο ἤσΘιον: αὐτὰρ ὁ τοῖσιν ἀφείλετο νόστιμον ἦμπαρ. τῶν ἁμόθεν γε, θεά, θύγατερ Διός, εἰπὲ καὶ ἡμῖν.

[Lattimore’s translation:]

Tell me, Muse, of the man of many ways, who was driven far journeys, after he had sacked Troy's sacred citadel. Many were they whose cities he saw, whose minds he learned of, many the pains he suffered in his spirit on the wide sea, struggling for his own life and the homecoming of his companions. Even so he could not save his companions, hard though he strove to; they were destroyed by their own wild recklessness, fools who devoured the oxen of Helios, the Sun God, and he took away the day of their homecoming. From some point here, goddess, daughter of Zeus, speak, and begin our story.

Comparing translations, tracing the etymology of words, and guessing the author’s intended meaning has always been a highlight of studying classics (this last point is less applicable to the Odyssey, which neither has ambiguous philosophy nor a sole author). During that winter semester of my sophomore year, I learned the nuances of Odysseus’ description as the “ανδρα…πολύτροπον” (line 1). Stanford’s commentary provides that πολύτροπον is ambiguous and can be taken to mean ‘much travelled’ or ‘of many wiles, versatile.’ Mandelbaum incorporated both meanings into his translation, in a rhyme nonetheless:

...the man of many wiles, the man who wandered many paths of exile...

Lattimore’s word choice, however, preserves the double meaning without expanding the two interpretations:

...the man of many ways...

I have not had the opportunity to read other translations of the Odyssey, like Emily Wilson’s, but I am anxious to read others over the course of the next year.

News of Nolan’s film no doubt has already caused anticipatory disappointment within the classics community, but an additional interpretation and depiction excites me, and has prompted me to pursue my long-held goal to read the entire Odyssey in ancient Greek. And honestly, when I first drafted this blog post, I had a more grandiose vision in mind than I do now. I would love to not only read it in Greek, but to study it in such depth that I would study the vocabulary, practice conjugating verbs, know all six principal parts (I know, I know), and read at least three full English translations before Nolan’s film comes out in 500 days! This would entail reading about 25 lines per day which is a worthy goal, but I am working towards other goals, which will be the topics of future posts.

I do however, want to maintain and improve my ancient Greek. I have decided that I will read 25 lines per day in various English translations, and I will deliberately and thoroughly translate 8 lines of those 25 that pique my interest. I will also have a page (maybe a single post with an updated date?) that marks my progress for sake of accountability.

This goal is subject to change as I see fit, but I wanted to have this post published by the T-500 days mark. Deadlines! Sheesh.

TL;DR – read Homer’s Odyssey in one form or another every day for the next 500 days, with at least some ancient Greek review, even if I can’t analyze it to the extent that I would like.

❦

Venturing on an epic voyage,

Ms. Alexander